Hanfu Knowledge

What is Hanfu? Understanding the Basic Characteristics and Styles of Hanfu

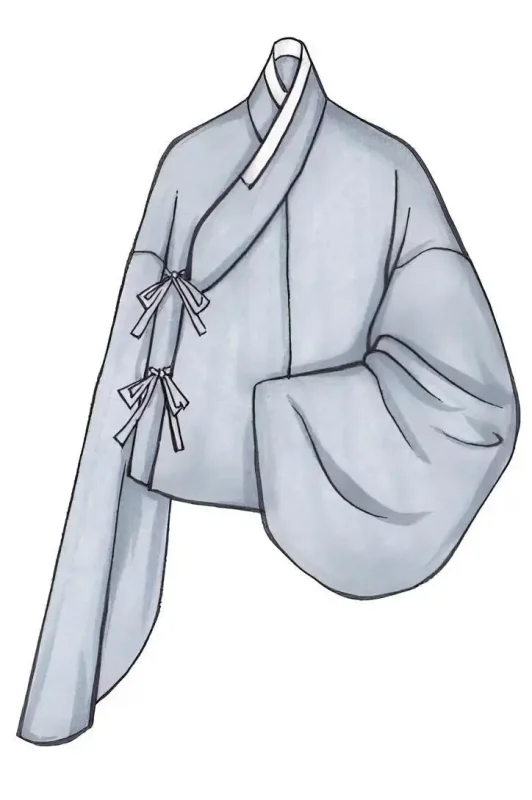

Hanfu does not refer to the attire of any single dynasty, but rather serves as the collective term for the traditional clothing system of the Han ethnic group. It embodies thousands of years of Chinese ritual culture, aesthetic sensibilities, and national spirit. From the overlapping lapels to the flowing sleeves, every detail reflects the ancient people’s profound understanding of the cosmic order and the aesthetics of daily life. Unlike theatrical costumes seen in films and dramas, authentic Hanfu adheres to rigorous stylistic conventions. Core features such as the crossed collar with right lapel, wide robes and sleeves, and concealed fastenings with ties make it a living repository of historical culture.

From the “deep robe” of the pre-Qin period establishing Hanfu’s fundamental form, weaving the principles of heaven, earth, and human relations into its folds; to the dignified elegance of the curved-hem robes of the Han Dynasty, becoming a classic symbol for ceremonial occasions; then to the graceful and flowing qixiong ruqun of the Tang Dynasty, embodying the openness and romance of the prosperous Tang era; the simplicity and elegance of the Song Dynasty’s beizi, outlining the refined and unassuming character of literati scholars; The intricate pleats of the Ming Dynasty’s horse-face skirt and the dignified grandeur of the stand-collar robe elevated Hanfu craftsmanship to its zenith. Each evolution of Hanfu remains inextricably linked to the prevailing social ethos and aesthetic sensibilities of its era, flowing like a winding river that carries the unique charm of Eastern aesthetics.

Basic Characteristics of Hanfu

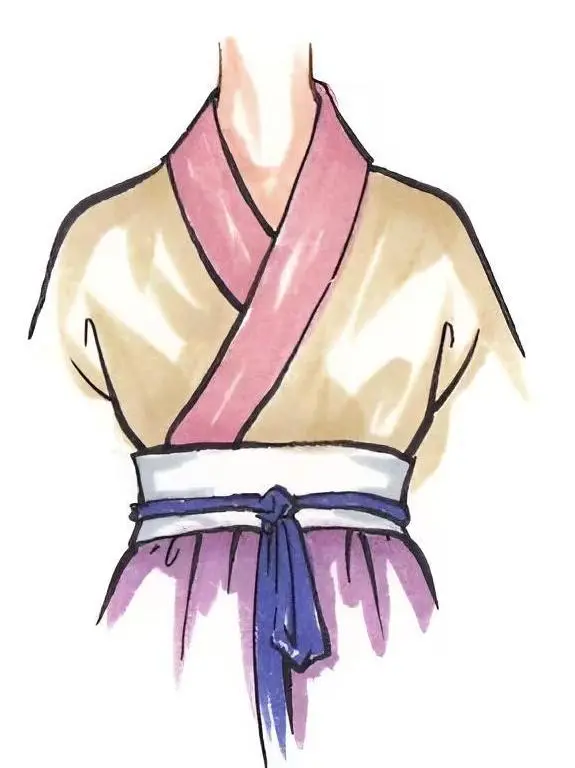

Crossed Collar with Right Lapel

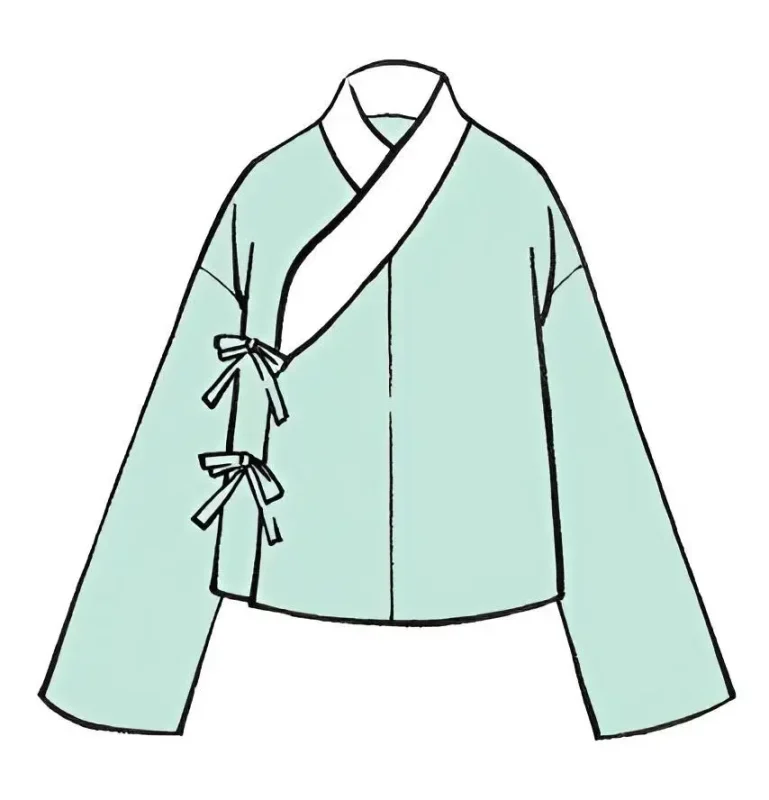

A crossed collar refers to the overlapping of the left and right collar edges, while the lapel denotes the front panel of the garment. “Crossed collar with right lapel” specifically describes a style where the left lapel overlaps the right, secured with a tie. From the outside, the collar forms a “Y” shape.

The right-lapel style is predominant in Hanfu for several reasons. One key factor is that the right-lapel design served as a significant identifier distinguishing Han Chinese attire from other ethnic groups’ clothing. Another widely held belief is that the living wear the right-lapel style, while the deceased wear the left-lapel style.

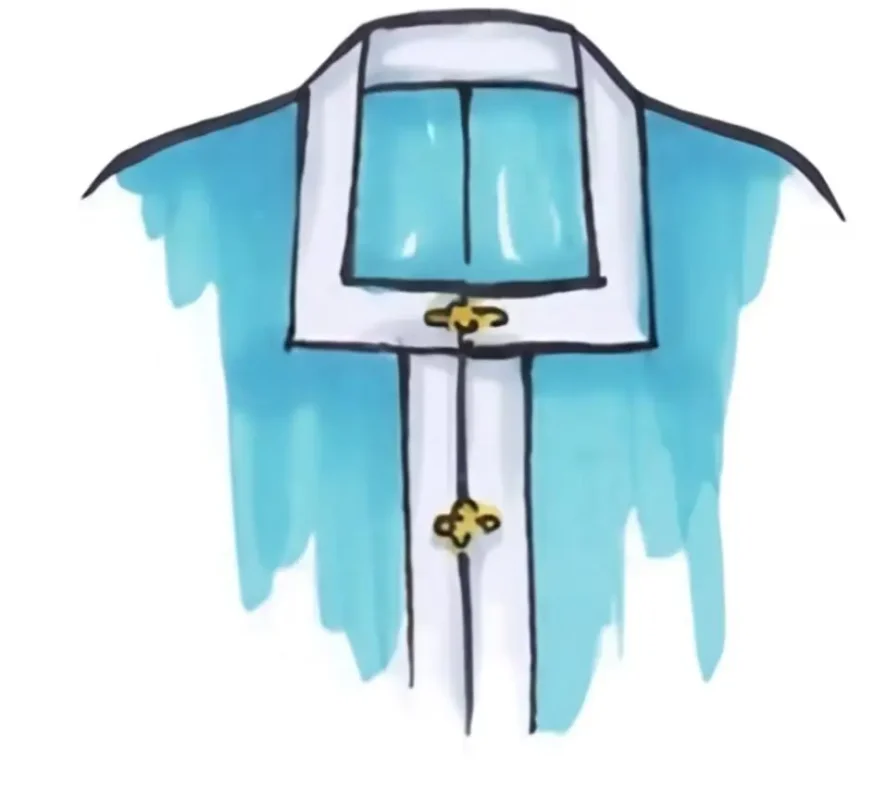

The crossed collar with the right lapel is a signature feature of Hanfu, but it does not imply that Hanfu exclusively features this collar style. Over its 5,000-year evolution, Hanfu designs have continuously refined and developed, giving rise to numerous other collar styles—such as the round collar popular during the Tang Dynasty and the stand-up collar prevalent in the Ming Dynasty.

Wide Garments and Large Sleeves

Compared to the fitted, form-hugging silhouettes of Western clothing, Hanfu typically features wide garments and large sleeves. While large sleeves are a prominent characteristic of Hanfu, they are not the only feature; Hanfu also includes everyday styles with smaller or narrower sleeves. The sleeves of Hanfu generally extend beyond the arms. When worn, the lines of the body appear as graceful as flowing clouds and water, conveying an air of magnanimity and composure.

While wide sleeves offer natural elegance, they can hinder movement and labor. Therefore, alongside the wide-sleeved style, Hanfu also features narrow-sleeved designs. Narrow sleeves are common in casual and everyday wear, while formal attire for ceremonial occasions predominantly employs the wide-sleeved style.

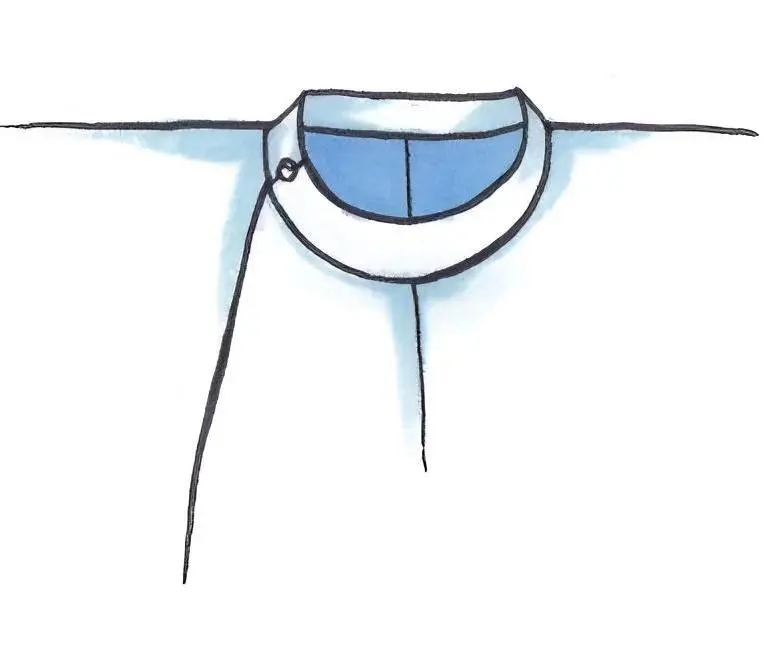

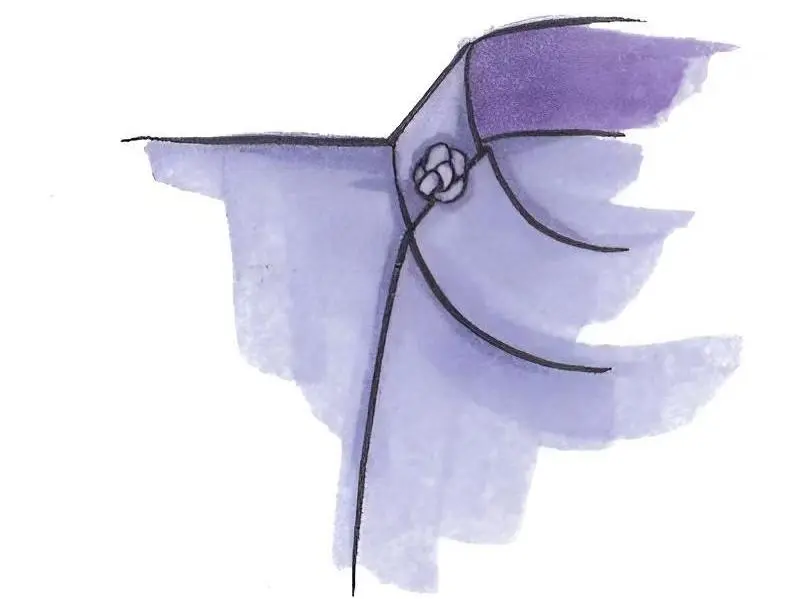

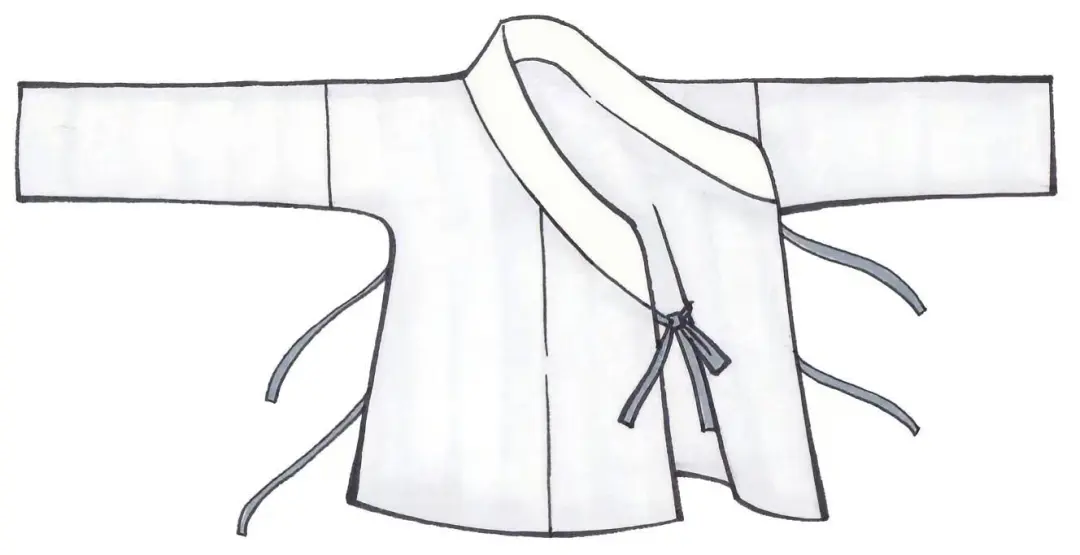

Tie-fastening

Hanfu features numerous fixed elements and styles, such as the fabric ties used on round-collared robes and the metal clasps on Ming Dynasty jackets. However, the most classic fastening method remains the tie-fastening. Positioned under the armpits, a pair of ties—one on the left, one on the right, one inner and one outer—work together to wrap the body tightly and securely.

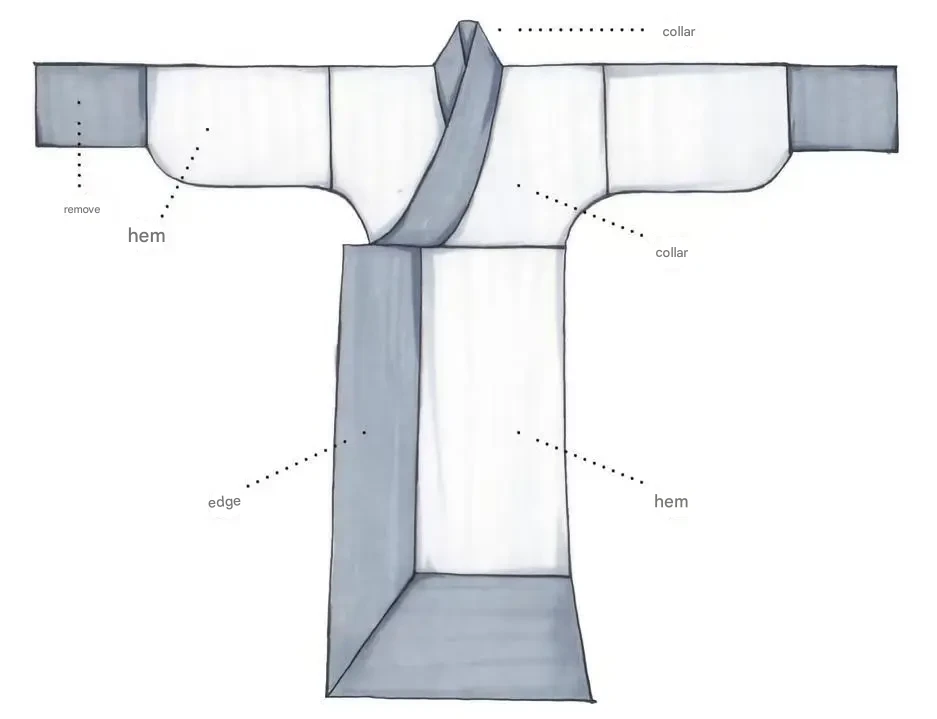

The Structure of Hanfu

Hanfu boasts a long history and diverse styles and designs, yet regardless of how the garments’ silhouettes evolve, their fundamental structure remains constant.

Hanfu consists of components such as the collar, sleeves, lapels, front panels, hem, and edging.

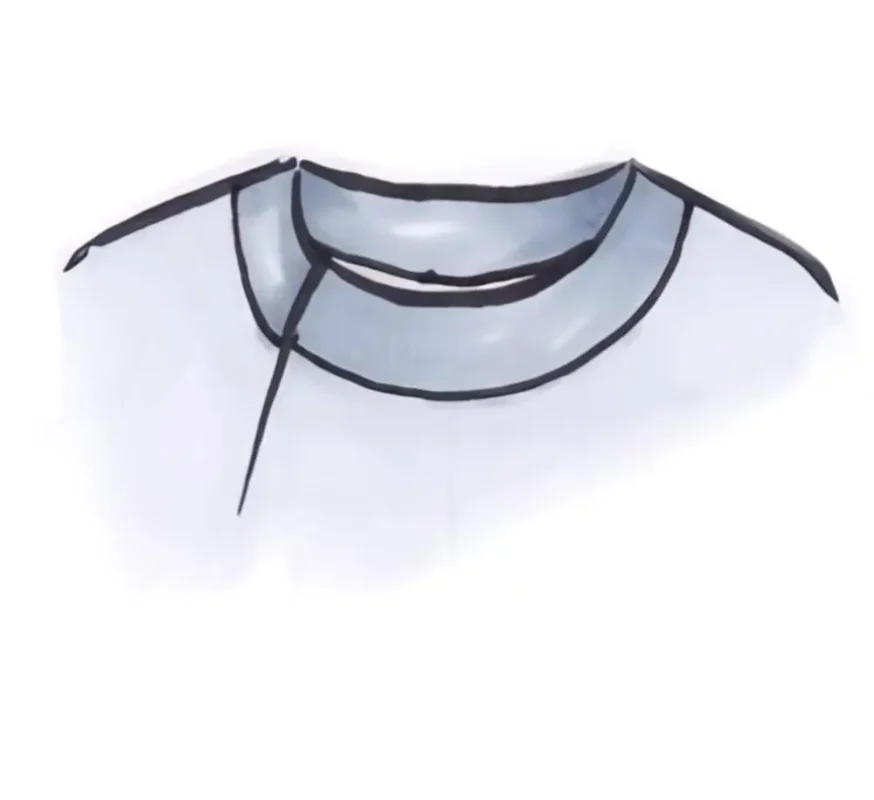

Collar

The collar refers to the part of a garment that encircles the neck. It can be categorized into various types, including the cross-lap collar, stand-up collar, square collar, round collar, open collar, and stand-up collar (non-Western-style).

Sleeve cuff

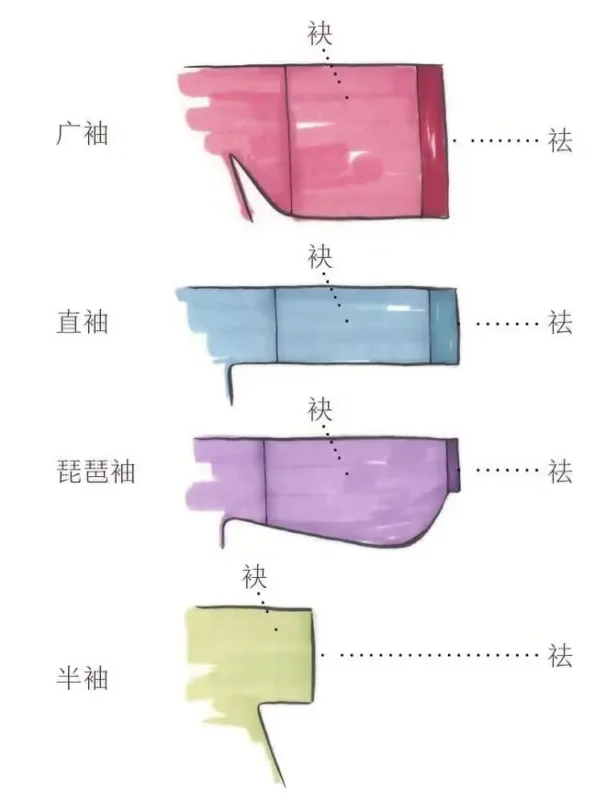

The sleeve cuff refers to the part of the sleeve that hangs down.

The sleeve hem refers to the part of the sleeve at the wrist.

The sleeve is composed of both the cuff and the hem. Common sleeve styles include wide sleeves (large sleeves), straight sleeves, pipa sleeves, and half sleeves.

Binding

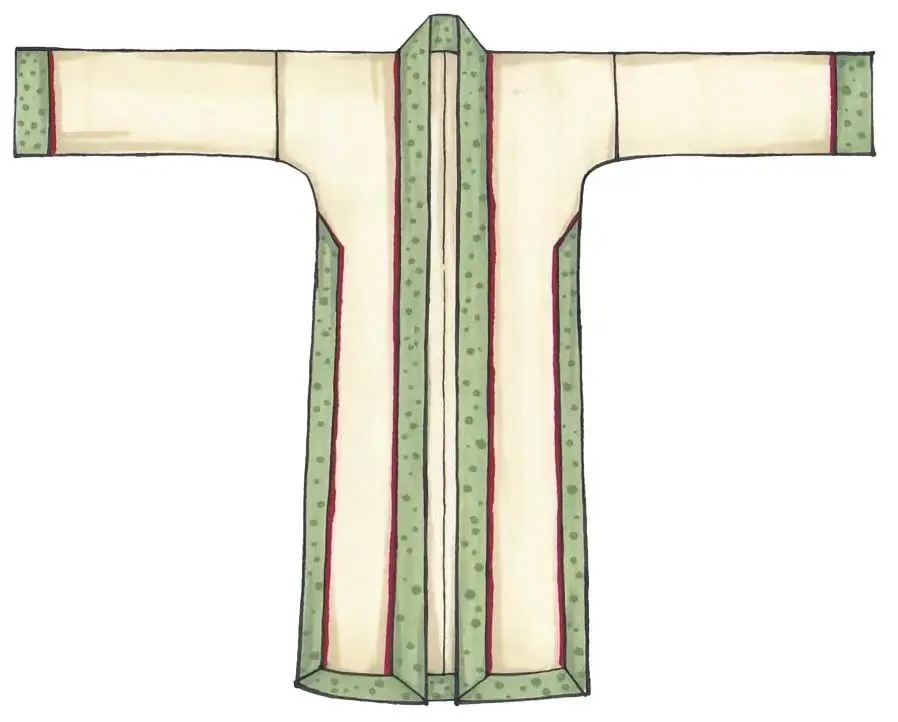

Binding refers to the edging applied to the edges of garments, such as collar edges and sleeve edges. Binding often uses contrasting fabrics to serve a decorative purpose.

The Design of Hanfu

The Hanfu we see today can be categorized into three main styles based on their tailoring methods: the robe-and-skirt style, the deep-robed style, and the all-in-one style.

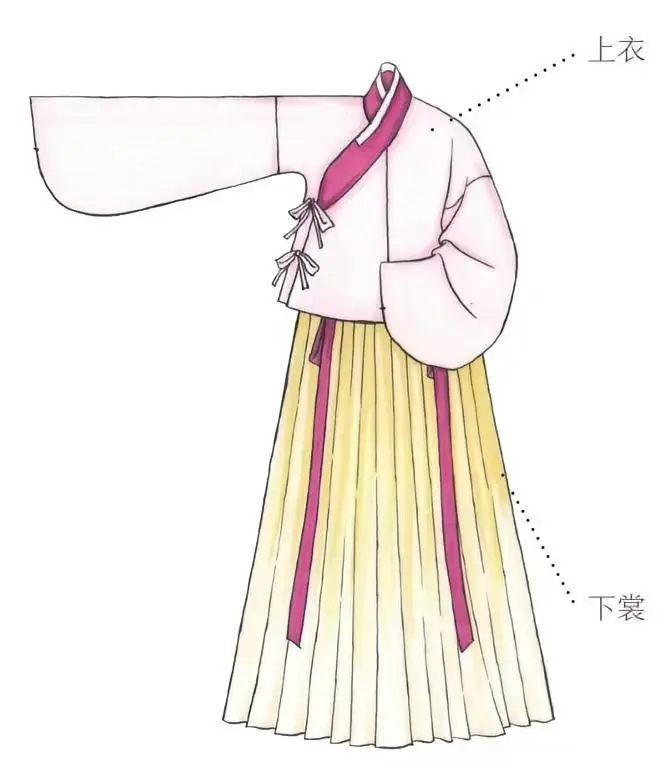

Uniform

The “upper garment and lower skirt system” refers to what we commonly call the “two-piece attire system.” The upper garments worn on the body, such as the ru, ao, and shirt, are called ‘衣’ (yī), while the lower garments worn on the body, such as skirts, are called “裳” (shāng).

In terms of craftsmanship, the upper garment and lower skirt in this system are cut and sewn separately, forming two distinct garments.

The upper-garment-lower-skirt system represents the most fundamental and ancient form of Hanfu. Both the deep-garment system and the one-piece-cut system evolved from this foundational structure.

Simultaneously, the upper-garment-lower-skirt configuration remains the most widely adopted wearing style, suitable for both men and women. This method of dressing is evident in both ceremonial attire and everyday clothing.

In modern Hanfu, the two most common garment styles are the ruqun and the aoqun.

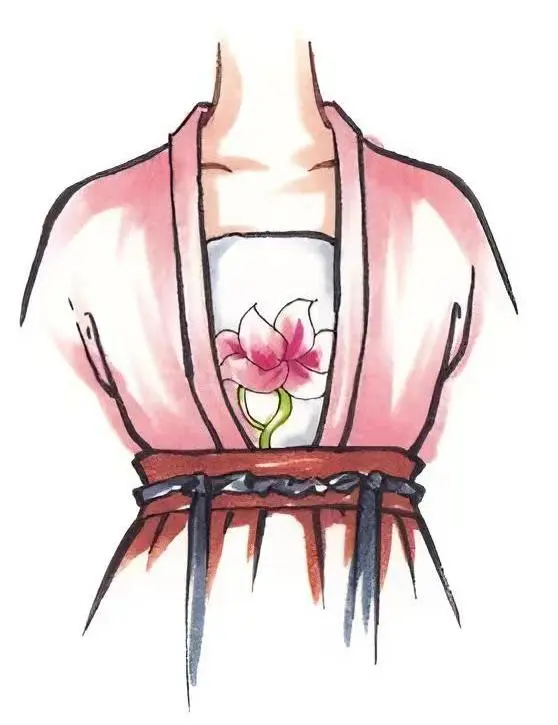

1. Ruqun

The ruqun represents a classic garment style, consisting of a short upper garment called the “ru” paired with a skirt to form the ensemble. Most Hanfu garments adhere to the principle that “a short top requires a long skirt, while a long top requires a wide skirt,” and the ruqun is no exception. Typically, the ruqun features a short upper garment and a long skirt. When worn, the ru is tucked into the skirt waistband, which is the most distinctive feature distinguishing the ruqun from other styles.

A single-layered upper garment is called a single-layer ru, resembling a shirt; a padded upper garment is called a double-layer ru, resembling a coat. The upper garment can be worn alone, layered over a camisole or strapless top, or worn over an outer garment like a hezi.

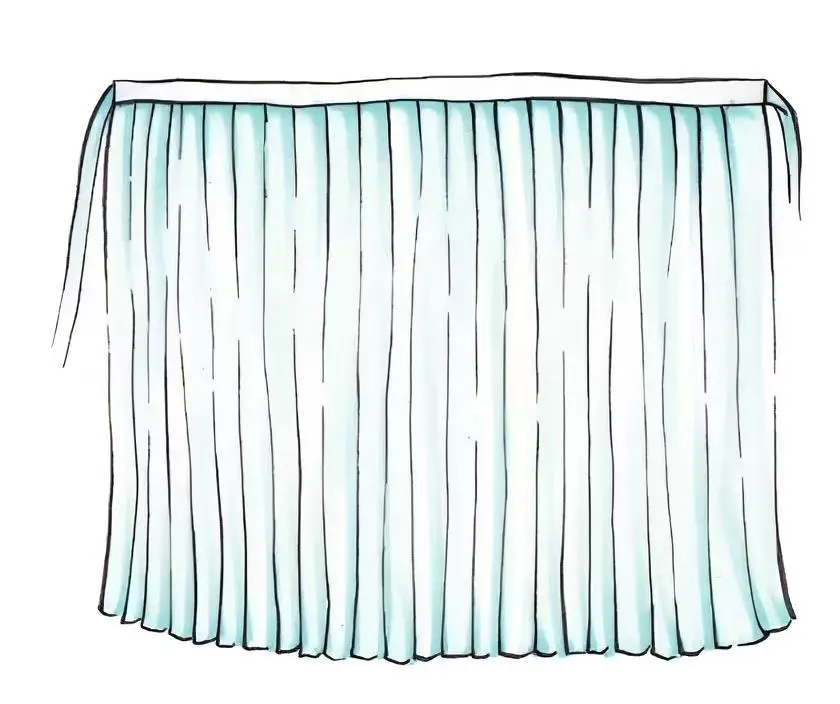

The lower skirt commonly found in ruqun consists of panel skirts and pleated skirts. Panel skirts are assembled from multiple trapezoidal fabric panels, while pleated skirts resemble the pleated skirts often seen in modern clothing. In addition to standalone panel skirts and pleated skirts, there are also lower skirts that combine the pleating technique of pleated skirts with the panel-sewing technique of panel skirts.

The ruqun was typically paired with accessories such as a draped sash and palace cord, which accentuated the graceful curves of a woman’s figure.

Ruqun can be categorized into cross-collared ruqun, front-opening ruqun, and open-neck ruqun based on the style of the upper ru’s collar. Depending on the height of the skirt waistband, they are classified as chest-length ruqun and waist-length ruqun.

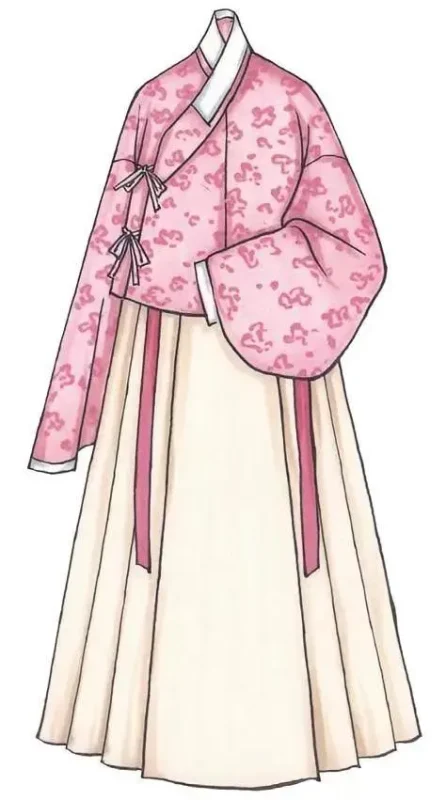

2. Ao-Skirt

Aoqun refers to the combination of wearing an ao (jacket) on the upper body and a skirt on the lower body, serving as a variation of the ruqun (jacket-skirt).

Records of aoqun date back to the Tang Dynasty, reaching its peak popularity during the Ming Dynasty. The aoqun we see in modern Hanfu are primarily “Ming-style aoqun,” designed based on Ming Dynasty artifacts and historical references.

The traditional way of wearing the ao-qun ensemble is “cloak over skirt.” The outer robe is worn on top, not tucked into the skirt waistband, with its hem covering the skirt’s top edge. In ancient times, a single-layer upper garment was called a “shirt,” while a padded upper garment was termed a “robe.” Today, the ‘robe’ in “ao-qun” primarily refers to the outer garment worn in this “cloak over skirt” style.

Outer robes are categorized by length as short or long, with the knee serving as the dividing line: those extending below the knee are long robes, while those above the knee are short robes. Ming dynasty aoqun developed a distinctive collar style—the stand-up collar (also known as the Ming stand-up collar)—building upon previous collar designs.

The lower skirt is typically chosen as either a pleated skirt or a horse-face skirt. Among these, the horse-face skirt, with its unique structural and decorative qualities, has become the most important style in women’s clothing.

Deep-robed attire

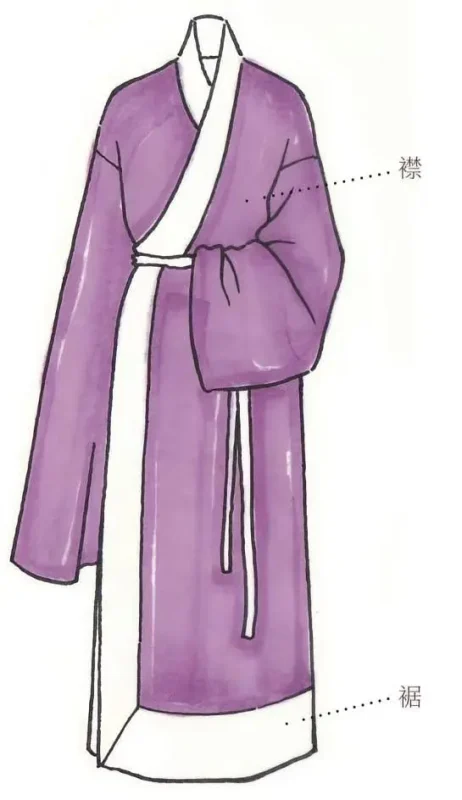

The deep-clothing style involves cutting the upper garment and lower skirt separately, then sewing them together at the waistline. Once completed, the garment forms a single piece, typically adorned with contrasting-color edging.

This garment style envelops the body tightly, concealing its contours. Due to its characteristic “deep and profound coverage,” it is termed the “deep-clothing” (深衣). The structural design of the “deep-clothing” shares a remarkable similarity with the dresses we wear today.

Hanfu garments in the deep-robed style can be broadly categorized into two types based on the shape of the skirt: curved-hem wrap-front robes and straight-hem robes. From the pre-Qin period to the Western Han Dynasty, curved-hem robes with wrapped collars gained popularity due to their ability to fully cover the body, eliminating concerns about exposure, while also alleviating the burden of prolonged formal sitting. Additionally, they were suitable for both men and women. Later, with improvements and refinements in undergarments, the wrapped-collar style became redundant. More convenient straight-hem robes gradually replaced the complex curved-hem robes with wrapped collars.

Additionally, it is worth mentioning the institutionalized Confucian deep-robed garment—the Zhuzi deep robe. This robe was reconstructed by the ancient scholar Zhu Xi based on the account in the “Deep Robe, Chapter Thirty-Nine” of the Book of Rites, incorporating his own interpretations. Nearly every detail of the Zhuzi deep robe embodies the principles of Confucian ritual education, and it was regarded by later generations as ceremonial attire for important occasions such as sacrifices and coming-of-age ceremonies.

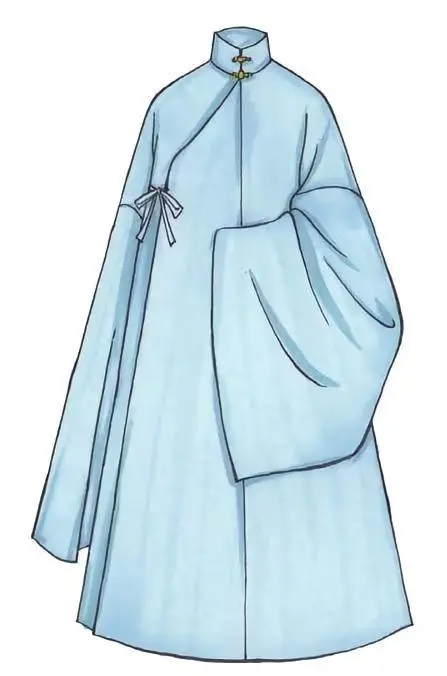

Through-Cut Style

The through-cut style of Hanfu features a continuous garment body, cut as a single piece from top to bottom without a waist seam. Compared to the deep-cloth style, through-cut garments are simpler and more conducive to movement, meeting the needs of people participating in increasingly frequent social activities. They gradually became an important style for everyday wear, such as the round-collar robe worn by both men and women during the Tang Dynasty.

By the Ming Dynasty, a style known as the straight-cut robe—featuring a cross-collared neckline, right-side lapel, wide sleeves with cuffed openings, and side slits—had become one of the classic designs in men’s attire. This garment could be seen in the wardrobes of everyone from emperors to scholars and commoners alike.

Additionally, there are two other styles remarkably similar to the straight-cut robe—the straight-hem robe and the Daoist robe, with the latter being a popular style among men’s everyday attire during the Ming Dynasty. The straight-cut robe, straight-hemmed robe, and Daoist robe are all open-fronted, long garments featuring a collar edge but no hem edge. The primary distinction lies in the presence of side panels at the hem: the straight-cut robe has outer side panels, the Daoist robe has inner side panels, while the straight-hemmed robe has none.